Previous Episode | Main Page | Next Episode

Lundy and Linda Khoy are sisters who both got in trouble with the law. They were arrested separately for intent to distribute ecstasy when they were in their teens. Both say they were rebelling against their strict parents in Virginia. The fork in their destinies can be traced back to where they were born – illustrating how a seemingly straightforward fact like birthplace gets codified in harsh immigration laws to create vastly different trajectories.

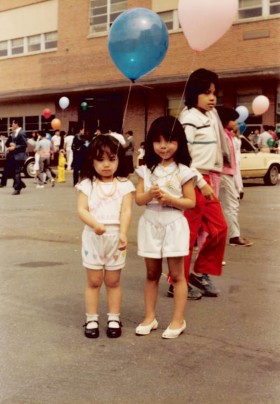

Lundy was born in a refugee camp in Thailand after her parents fled Cambodia’s genocide. Like millions of other Southeast Asians displaced from the region due to US aggression, the family was brought to the United States through a refugee resettlement program, and Linda was later born in California. As they adjusted to life here, Lundy and her parents, who received Green Cards (or permanent residence status), didn’t know how to become U.S. citizens.

Linda’s arrest at 19 years old involved hundreds of pills of ecstasy. As a U.S. citizen, Linda served a year in prison and when she was released, she got on with her life. Lundy, on the other hand, was arrested with just seven pills. The judge suspended her sentence and put her on probation so she could go back to school, but now she is facing deportation. Even though Lundy married a US citizen and has a US citizen child, an immigration judge ordered her deported. Through her activism with groups like the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC), Immigrant Defense Project (IDP), and the Immigrant Justice Network (IJN), Lundy secured a pardon from the Governor of Virginia. But the risk of deportation still looms.

Immigrants with criminal convictions have been increasingly demonized by the Trump Administration. Alongside hateful and racist rhetoric, Trump’s executive orders set into motion an indiscriminate deportation machinery, blind to the realities of people’s lives: their children and families, how long they have been in the country, what they have contributed to their communities. Because of changes enacted in the 1996 immigration laws, many non-citizens (including longtime residents like Lundy) face mandatory deportation for a broad range of offenses, including minor drug charges.

Immigrants with criminal convictions have been increasingly demonized by the Trump Administration. Alongside hateful and racist rhetoric, Trump’s executive orders set into motion an indiscriminate deportation machinery, blind to the realities of people’s lives: their children and families, how long they have been in the country, what they have contributed to their communities. Because of changes enacted in the 1996 immigration laws, many non-citizens (including longtime residents like Lundy) face mandatory deportation for a broad range of offenses, including minor drug charges.

Southeast Asian American refugees have been disproportionately impacted by harsh laws designed to deport anyone with an old criminal record. Of all deportation orders to Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam since 1998, almost 80% were due to old criminal convictions. The vast majority of these are people who came as babies and children fleeing war and genocide with their parents. Because these countries accept only a small number of deportees, around 12,000 community members like Lundy are living day-to-day with final orders of deportation, rebuilding their lives and raising families, all the while knowing that the threat of deportation looms over them. Lundy calls this a “life sentence.”

|  |  |  |  |

Episode Transcript

Linda Khoy: Hi. Come here. Come here.

Will Coley: Linda Khoy runs a dog walking business in Northern Virginia.

Linda: He likes to pull a lot so…

WC: Linda is worried because any day now Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, could deport her sister Lundy.

Linda: It’s tough you know. In fact, I definitely feel guilty in some ways.

WC: Why? What do you feel guilty about?

Linda: Just… She has to go through this.

WC: But why? How is that your fault? I mean?

Linda: It isn’t but it’s still like. Like why’d I? Why’d I get lucky? That’s where the guilt comes around.

WC: You are listening to Indefensible.

Trump: We do not need new laws. We will work within the existing system and framework. We are going to get the bad ones out.

Quyen Dinh: Individuals who were welcomed into this country as babies, as children, as refugees from war torn nations facing deportation back to countries that they fled in which many have never known.

Bill Hing: There’s no reason to deport someone like Lundy. She represents people who made a mistake who deserve a second chance.

WC: Stories of people resisting deportation. This is Will Coley.

WC: Linda Khoy’s sister, Lundy, lives in Washington, D.C. Hi Lundy.

Lundy: Hi Will, nice to meet you.

WC: Nice to meet you. She’s put together and kind of girly.

Lundy: My name is Lundy Khoy and I am facing deportation.

WC: And here’s Linda, the dogwalker who unlike her sister, is a U.S. citizen.

Linda: My name is Linda Khoy and I am Lundy’s younger sister. I’m very much gay. Obviously, I’m gay. I’m pretty sure it’s obvious.

WC: Lundy and Linda have a lot in common. Both sisters got in trouble with the law when they were each 19 years old and both of them for attempting to sell the drug ecstasy. But what happened to them next depended on where they were born. Remember Linda is a U.S. citizen and Lundy is not. The difference is clear by looking at their birth certificates.

Linda: My sister’s looks like a crumpled piece of yellow paper that had some writing on there.

Lundy: And yours were so nice and you know a nice piece of paper and so official.

Linda: So, official.

WC: Lundy and Linda’s parents fled the murderous regime of the Khmer Rouge, ruling party in Cambodia. Lundy was born in a refugee camp in neighboring Thailand. The family was selected for refugee resettlement to the United States.

Lundy: And then soon after um that, me arriving in the U.S. Linda was born a year later. And it already felt like I was different at a very young age because I knew I had a Green Card. and I was referred to as an alien. And I thought that you’re only. You’re only a U.S. citizen if you were born here and you only have a right to vote if you were born here. No one contacted my parents or said, ‘Hey guess what? You’ve been living here for five years. You have your legal permanent resident. Now you can go ahead and apply for your citizenship.’ I didn’t know there was a big difference. Now I do know once I got in trouble with the law.

Linda: I was under the same presumption as Lundy. My parents were only concerned about making sure the kids were fed and that they’re not having any issues in school and there’s a roof over their head. They’re just so happy to be able to have a place for the kids that they can continue to have hopefully a better future than they had back at home.

WC: And thousands of other Cambodian families were also adjusting to life in the States. More than 158,000 came to the U.S. between 1975 and 1994.

Bill Hing: My name is Bill Hing and I am a law professor at the University of San Francisco and also the founder of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. The vast majority of Cambodians that have been deported are individuals who entered the country as infants and toddlers and grew up in the United States. It’s very clear that their parents all suffer from post-traumatic stress when they entered and that really affected how they tried to adjust in the United States. And if you couple that with the fact that these are refugees, they are people who enter the country and they’re poor and they’re kids are basically products of the socioeconomic situation in which they have been thrust into in the United States as refugees.

WC: Lundy says that her parents were very strict. They had traditional ideas of what girls could and couldn’t do. Her father wanted to know where she was at all times. He didn’t allow her to join any high school clubs and programs.

Lundy: And when I went to college I just wanted to have friends ‘cause I really didn’t have a ton of friends. So it opened this whole new door of like freedom.

WC: Linda, the one who’s a U.S. citizen, agrees.

Linda: We didn’t know what freedom was supposed to look like. I just remember my first day of college. I was relieved but also scared.

Lundy: You felt unprepared.

Linda: Very unprepared. It was really too soon. It was just a complete shock and that’s when I really started doing things that were not right.

WC: Lundy, the one facing deportation, had a similar experience.

Lundy: So, I just went along with the group that were nice to me you know and the guy I was dating at the time, you know was older and he had a car. He was the tennis player and he liked me so I went along with it. But then he slowly introduced me to a different style of partying and he’s the person that gave me my first ecstasy pill.

WC: What was that like?

Lundy: So, ecstasy opened this door of like being able to communicate. It was easy for me to connect and talk to people where else the Lundy before didn’t because I didn’t. I never found my own voice. The ecstasy when I first took it was just fun. So, I liked that. And now looking back on it, it was just all an illusion I felt like now you know. And it was like literally just a short period of time until I got caught you know. I’ve heard about heroin and coke and those conversations like in school. You know like don’t do drugs. But I didn’t know anything about ecstasy that it was an illegal substance. I just know that it. It makes you feel good.

WC: Lundy’s boyfriend convinced her to take money from her mother to buy ecstasy pills for their friends. But when they had extras they decided to sell them, something Lundy had never done. Lundy and her friend went to the Arlington Metro stop and asked someone if they’d heard of ecstasy. That person told the police who then stopped Lundy. They asked her what was going on.

Lundy: And he was like, “Do you have some on you right now?” I was like, “Yeah I have seven of them in my purse.” Like I didn’t know this was like a bad thing you know ‘cause the. The drug made me felt good. I didn’t know how, why this is a bad thing. And they were just looking at me really weird and they’re just talking to each other and they’re like, “Do you know that you’re. you’re going to face up to ten years?” And then that’s when I was just like, “Oh my God. What did I just get myself into?” Like what? And they handcuffed me and then um took me to jail.

WC: Lundy was locked up for two nights. Because she was suicidal they put her in the psych unit. When Lundy was released she went home and told her parents she had been doing drugs. Her sister Linda was there. “Do you remember that day?”

Linda: I do. I do. It was just difficult. Very difficult. At that moment, I knew my dad was. He was so mad but he was just really sad for my sister to. To what happened to her.

WC: Lundy went to court and plead guilty but her lawyer didn’t warn her about the implications for her immigration status. Lundy stayed in jail for four months until she was sentenced. The judge decided to release Lundy on probation.

Lundy: I always will remember what she said. “You were just dumb, naïve girl.” You know. And I… I felt that way.

WC: During the year 2000, Lundy regularly went to her probation meetings. During that same year, her U.S. citizen sister Linda, enlisted in the Navy and planned to ship out in a few months. Even though her sister had been arrested, Linda had her own run in with the law.

Linda: At that time, I was already partying as well.

WC: Linda had started dating a woman named Yasmine, who was into ecstasy.

Linda: And she really got involved in that drug. Like she just really fell in love with it. And then she really wanted to make a business out of it.

WC: Linda’s girlfriend started selling the drug. Because Linda loved her, she went along for the exchanges.

Linda: So, on the fourth exchange um I just remember sitting in the car. This time it was taking like really long. Normally it’s a good five, ten minutes and we’re on our way and get something to eat. So, I just closed my eyes and I literally opened my eyes and there was just like seven or eight squad cars surrounding us. And they, you know, they pulled me out of the car, put me in a separate car.

WC: The police took Linda in for questioning. She thought her enlistment in the Navy would protect her. When they asked why Linda was there she said,

Linda: Because she’s my girlfriend and I’m very much a part of this. that’s what I said. And it’s all it took.

WC: Linda went to prison for a year. While she was there her sister Lundy, continued to follow the rules. She passed her drug test, paid her court fines, went back to school. She saw her probation officer as a mentor. But then in 2003 her probation officer sent her a letter requiring her to come for an additional appointment outside the normal schedule for her check ins. Lundy thought it was strange but went anyway.

Lundy: So, I go through the door. The door shuts behind me and I see all these officers in their like windbreakers that had ICE on it. And they’re. and one lady, she was like, “Are you Lundy Khoy?” And I’m like, “Yes.” “Okay please stand against the wall.” Um they took my bag and they’re like, “Spread your legs” and they’re just patting me. And then she then is reading like, “We’re detaining you for your offense and you know we’re… I’m like looking at my probation officer like, “What the fuck?” She does this with her hands like, “I’m so sorry.” You know. And she said, “What can I do?” I was like, “Can you please go out and contact my family?” What I was worried about is actually happening.

WC: When she was in jail she heard that Green Card holders could be deported. Lundy brought this up to her probation officer on their first meeting.

Lundy: And she’s like, “No you have nothing to worry about.” ‘Cuz she was like, “There’s more serious stuff you know to deport people for. Like they’re not going to care about little old you.”

WC: Lundy ran into U.S. Immigration Law which deems a range of criminal convictions grounds for deportation, no exceptions. And after September 11th immigration enforcement began looking for people to remove from the U.S. Unbeknownst to Lundy, in 2002 the United States took steps to make it easier to send Cambodian refugees back to Cambodia. Professor Bill Hing explains.

Bill Hing: The United States government through the State Department, actually entered into a memorandum of understanding with the Cambodian government to begin accepting back to Cambodia, individuals who have been convicted in the United States of serious crimes. And Cambodia was threatened by the United States that if it did not sign this memorandum of understanding that foreign aid would be cut off. And so, Cambodia signed this repatriation agreement and. And since that time, several hundred Cambodians who have been deported to Cambodia.

WC: Linda remembers the day that her sister got detained by immigration.

Linda: I remember answering the call and it was Lundy’s probation officer. They basically said that this was something I wish I didn’t have to do to your sister. But ICE detained her to deport her. So, in my mind I’m like, ‘Oh my God!’ Like they’re about to take our sister away. I gotta call our parents. I don’t know what I can do about this yet. And it was tough because Lundy did everything for the family. And at that moment I was like, ‘I need to really step up and figure this out.’ Eventually Lundy was able to call us. I don’t know how many days later. You weren’t able to call us. But eventually she was able to call us and let us know where she was. She was at Hampton Roads which was like a good hours away. Like a four or five hours away.

Lundy: Four or five hours.

Linda: And um. And then I remember coming to visit her. Um.

Lundy: Twice.

Linda: Yeah we. We visited twice. Well it would have been three times but one time we actually went there and there was a lockdown and they wouldn’t let us go in. We didn’t know what was going to happen.

WC: Immigration detention wasn’t easy for Lundy.

Lundy: Um for me it was a scary a time because you don’t know how long you were going to be in there. I was there for nearly nine months. So, they can’t just put me on a plane and take me to Cambodia without any form of travel document. And for them to get a travel document they have to contact the Cambodian embassy. Well the Cambodian embassy was like, “Well she wasn’t born here. Like how do we know she’s Cambodian?” You know, I remember some of the folks that were in there, they were there for years. It was just so sad and. And that’s what I mentally prepared myself for. That this. this is reality right now Lundy and this might be your reality in the future for a really long time. You’d better get used to it.

WC: But right before Christmas the deportation officer at the facility suddenly told Lundy that she was being released. Turns out they couldn’t get travel documents necessary for deporting her. Since Lundy was born in a refugee camp, neither Cambodia nor Thailand claim her as a citizen. Since ICE can’t deport her, Lundy has to check in regularly with their office. For several months, she had to wear an electronic monitor on her ankle. Are you still in fear that they’re going to come and rearrest you?

Lundy: Yes. Yes. Um yeah ‘cuz you just never know. You know now that I’ve experienced this um you know from the age of nineteen, with the system it’s just. You just. Nothing is guaranteed.

WC: Lundy became an advocate. She now works for an advocacy group, The Southeast Asian Resource Action Center or SEARAC in Washington, D.C. just across the Potomac River. SEARAC recently organized an informational briefing for Congress people on Capitol Hill. Lundy and Linda were invited to tell their stories. We meet outside with other participants before entering. (on tape)Have you. Have you testified with your sister before like this?

Lundy: Not with my sister. This would be the very first time to have my sister share her story and um my story.

WC: Where are we going?

Lundy: Following the group.

Linda: I saw the herd of Asians right. It’s kind of.

Lundy: Yeah, I know we’re going to the Cannon building.

Linda: My God the line keeps getting longer. Okay.

WC: The briefing is in a small conference room.

Quyen Dinh: Good morning everyone. Good morning. My name is Quyen Dinh. I am the executive director of SEARAC, the South East Asian Resource Action Center.

WC: All together Cambodian, Vietnamese and Laotian refugee communities are the largest group of refugees ever resettled in the United States.

Quyen Dinh: Since 1998 over 13,000 Cambodian, Laotian and Vietnamese Americans have received final deportation orders. These policies have resulted in southeast Asian Americans with legal status but no citizenship, being three to five times more likely than other immigrants, to have been deported because of expanded definition of aggravated felonies that would subject 65 million, or one in four Americans to be deported.

WC: First up, are Lundy and Linda.

Lundy: I showed up at SEARAC. I sat there and I said to them, ‘I’m tired of being scared. And I don’t want to sit here and be sent back to a country I’d never been to before. So, I want to fight back.’ So, I became an advocate. So, this is my story. My reality. And I’m going to pass it over to my sister for her to share something personal as well.

Linda: Good morning. Um sorry. I get a little emotional over this. it was funny ‘cause Lundy asked me if I wanted to come speak and I’m like, ‘No I do not. Please stop inviting me.’ But I came. I came because she needs the support. And this is a very serious situation that needs to be changed. I was incarcerated as well for a year. Because I also was convicted at the same exact age as Lundy. We both made mistakes. We served our time and we want to be able to move on past this. and as I mentioned I certainly can but Lundy can’t. it’s just not fair. That’s our story.

WC: Lundy is 35 years old and has now been fighting to stay in the United States for nearly 14 years. The Trump Administration says that immigrants with criminal convictions will be at the top of the list for deportation. But Lundy continues to resist. She refuses to be separated from her family. After the hearing, I visit Lundy at the home she shares with her husband and their baby in D.C.

Lundy: Do you want to say something? What were you trying to say? Mommy’s trying to fight and stay here in the U.S. so I can watch you grow. My sister and I sat down and wrote a letter to the governor and put in an application for my pardon.

WC: Lundy gathered the news articles written about her situation and noted all the briefings she had done.

Lundy: The package that I mailed to the governor’s office was about 700 pages.

WC: Professor Bill Hing advised Lundy on the pardon process.

Bill Hing: The role that I played was explaining to the governor’s office why it was important for them to grant a pardon. In Virginia unfortunately, the only way you can get a full pardon is there is actual evidence that you are not guilty. And she was guilty of the ecstasy possession. And so, they just grant her a simple pardon where it’s the type of pardon where you don’t have to report it on your employment applications and that type of thing. But it’s still there. Unfortunately, Lundy still has this hanging over her head because even though it was just a few tablets of ecstasy, it’s considered an aggravated felony.

Lundy: (baby babbling) And what happened? Tell us what happened. Basically the governor says that you know I am… I changed my life around and that they have forgiven me for the crime. So, it was…It was such an accomplishment. Like we felt like we won something, even though it doesn’t guarantee my stay. But it showed that the governor was very human you know. That he believes in second chances and that’s what it felt like he was giving me, is another chance. Now if only I can get ICE to see that. It doesn’t guarantee that I’m safe. I could still be deported ‘cause I committed the crime. So that was really disappointing to hear. Um ‘cause it’s such a scary thing to just… Now even more scarier because I have my baby. The idea of him being separated from me you know and this law… it exiles people from their home. It’s like you know you’re in part of a tribe and you made a mistake and then you’re being sent away to survive on your own. And it doesn’t make any sense.

WC: Lundy reports to ICE once a year for a check in, sort of like her earlier probation meetings. Her deportation is stalled because they don’t know where they’d send her back to. That may change soon.

Bill Hing: There’s no reason to deport someone like Lundy. She’s not hurting anyone. Just happened when she was a teenager and you know she’s led. You know a clean and productive life. And now she’s got a family.

Lundy: I believe in second chances.

WC: This February the Trump Administration announced drastically expanded priorities for deportation. This includes people with prior criminal convictions but also those who have only been charged with a crime. The memo doesn’t mention people who have no country to return to. Despite this announcement many families are holding out, fighting to stay together. They say that they are here to stay.

WC: You’ve been listening to Indefensible. This podcast is brought to you with the support of the Immigrant Defense Project and the Four Freedom’s Fund. Andrew Ingkavet composed the music. KalaLea edited this episode and Ann Pope is our audio engineer. Special thanks to Sara Burningham, Lucy Kang, Loris Guzzetta, Ruth Morris, Caitlin Pierce, Church World Service and SEARAC. Join us next week for another episode of Indefensible. Be sure to subscribe on iTunes or wherever you get your podcasts.

|  |  |  |  |